Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg and Cagliostro — A Mystical Collaboration

Fra:.Uraniel Aldebaran

33°, 90°, 97°, 98° SIIEM, 99° Hon WAEO, K:.O:.A:.

Order of Ancient and Primitive Rite of Memphis and Misraim

Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg (1740-1812), a French artist who became the youngest member of the French Academy of Painting in its history in 1767, moved from Paris to London in 1771. This relocation became a turning point in his career. Over the next fourteen years, de Loutherbourg distinguished himself as an outstanding master of theatrical art, introducing innovative solutions in set design, the use of lighting effects, and sound automation. His work at the Drury Lane Theatre brought him widespread fame and recognition in London society.

De Loutherbourg was born in Strasbourg in 1740 into a family of artists. His father and uncle were well-known miniaturists, which predestined his interest in art from an early age. Beyond painting, de Loutherbourg was fascinated by science and technology. He experimented with electricity, optics, and acoustics, which helped him create astonishing stage effects that were ahead of their time. In 1781, de Loutherbourg’s talent and innovation were recognized with his election to the Royal Academy of Arts in London. He also had the honor of working as an artist for the British royal court.

However, like many foreign artists of that time, de Loutherbourg harbored a deep interest in alchemical mysteries and occult sciences. He assembled one of Britain’s largest collections of rare books on magic, astrology, Kabbalah, and hermetic philosophy, and equipped a well-furnished laboratory for alchemical experiments. This interest in esotericism was characteristic of the Enlightenment era, when many great minds sought to comprehend the hidden forces of nature and uncover ancient mysteries of existence.

Despite the triumph of rationalism and scientific thought, fascination with occultism, secret societies, and mystical teachings was widespread among intellectuals and aristocrats of the 18th century. The popularity of Freemasonry, which united enlighteners and freethinkers, and the emergence of new esoteric movements such as mesmerism and Swedenborgianism, reflected the spiritual quests of Enlightenment-era people who yearned for illumination and unity with higher powers. Egyptian themes and symbolism also came into fashion, especially after Napoleon’s famous expedition to Egypt in 1798-1801 and the publication of a luxurious illustrated description of this mysterious country.

Against this background, it is unsurprising that de Loutherbourg was captivated by the extraordinary personality and impressive Masonic credentials of Count Alessandro Cagliostro (1743-1795), the famous Italian adventurer, alchemist, and occultist. Although de Loutherbourg officially belonged to the respectable London Grand Lodge, meeting social expectations, he also secretly joined several less orthodox lodges and societies both in England and on the continent. For the artist, the arrival of Cagliostro, known as the “Great Copt,” was an event of international significance, as the count was considered one of the most influential and mysterious Masons of his time.

In 1785, Cagliostro became embroiled in the scandalous “Affair of the Diamond Necklace” — a scheme involving forged letters of Queen Marie Antoinette to acquire jewels. Although the count was acquitted in a sensational trial, his reputation was damaged, and he was forced to leave Paris. But before this loud scandal, Cagliostro’s popularity had reached its zenith, and he decided to expand his influence by turning to art.

Seeking to spread Egyptian Masonry in England, Cagliostro decided to utilize de Loutherbourg’s artistic talent. In autumn 1786, the count convinced the artist to create a series of symbolic paintings for the initiation rooms in a new lodge he intended to establish in London. This lodge was meant to become a center of Egyptian Masonic rituals, attracting aristocrats and wealthy citizens with mysterious promises of spiritual enlightenment, alchemical secrets, and contact with angelic beings.

Following Cagliostro’s detailed instructions, de Loutherbourg painted eight watercolors, allegorically depicting the trials that a female neophyte must undergo on the path to initiation. The choice of a female character reflected the special role that Cagliostro assigned to women in his Masonic system, unlike most lodges of that time which admitted only men.

The first painting shows the goal and future trials of the initiate in symbolic form — a sensual young woman in white garments with a blue sash (an idealized image of Serafina, Cagliostro’s wife) gazes passionately at a shining sacred city in the clouds, but her path is blocked by a fearsome green serpent. This image alludes to the biblical story of Eve’s temptation by the serpent in the Garden of Eden and the necessity of overcoming temptations on the thorny spiritual path.

The second painting depicts the neophyte, having successfully reached the second degree of initiation, symbolized by the ruins of a classical temple with treasures scattered across the floor. Her right hand grips a sword with which she has just severed the serpent’s head, while her left hand is pressed to her chest in sign of a solemn oath. This subject emphasizes triumph over temptation and the acquisition of spiritual strength through overcoming obstacles.

In the third painting, the neophyte is immersed in contemplation of the next stage of trials. With downcast eyes, she stands before a lady — the Grand Master of the lodge wearing a helmet adorned with Athena’s owl, the traditional symbol of wisdom. The lady points to a winding mountain path where menacing hermaphrodite witches congregate, personifying carnal passions, vices, and illusions. This is a reminder of the need to overcome base instincts and deceptive visions on the path to true enlightenment.

The fourth painting shows the neophyte at the foot of a majestic Egyptian pyramid, above which shines a brilliant rainbow — symbol of divine covenant and the connection between heaven and earth. This is a moment of deep despair — she sits exhausted on a stone, tired, with a broken sword at her feet, while witches with sagging breasts and snakes crawling from their genitals perform a diabolic dance on the path, waving burning torches and writhing bundles of snakes. In the center of the composition rises the “Great Copt” himself in ceremonial robes with a sword and mitre, authoritatively inviting the candidate to undergo the initiation rite before the temple portal. This scene symbolizes a crisis of faith and moral dilemma, when the coveted goal seems unattainable and the temptations of the flesh almost overcome the powers of the spirit.

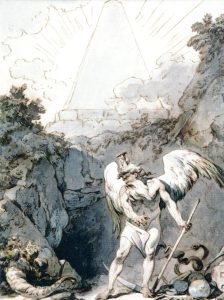

In the next painting, the initiate confronts the greatest existential horror — the specter of inexorable death. At the entrance to a dark grotto beneath the temple is drawn the gigantic figure of a threatening winged elder with a flowing beard — this is Father Time (Chronos) with an hourglass on his head and the scythe of death in his bony left hand. His sinister intentions are obvious — he is ready to mercilessly cut the thread of life of the trembling candidate. This eerie motif of memento mori (remember death) reminds of the transience of earthly existence and the inevitability of the end for each mortal.

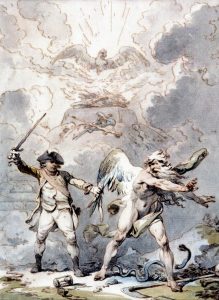

But at the critical moment, when hope for spiritual rebirth seems lost, the “Great Copt” himself comes to the rescue in the recognizable form of a slightly thinner Cagliostro with a scarlet order sash across his shoulder. He decisively grabs Chronos by the wings, raising a gleaming double-edged sword over him to sever them with one stroke. In the foreground, the sinister hourglass is overturned, and behind the Copt’s back, a fiery phoenix rises from a funeral pyre with a triumphant cry — an emblem of victory over death. Time, humanity’s eternal enemy, is overthrown, and death is conquered by the immortality of the enlightened soul through the mystery of initiation into eternal truths of existence. This paradoxical allegory with a hint at the alchemical process of matter transmutation expresses fundamental Masonic ideas of purification, rebirth, and attainment of spiritual perfection.

But the Copt must fight one more formidable opponent on the path to final triumph — a winged figure in a flowing chiton and winged sandals. However, this is probably not Hermes Trismegistus himself, the legendary founder of hermetic philosophy from whom Cagliostro traced the origins of his “True” Egyptian Masonry, but rather his distorted image, the false god Mercury (Hermes), worshipped in the profane rituals of orthodox Freemasons. At the height of an intense battle, Cagliostro, with a skillful lunge, pierces the false Mercury’s heart with his sword’s point, striking him dead to the ground. This cosmic-scale duel symbolizes the superiority of Cagliostro’s esoteric “Egyptian” Masonry over exoteric, traditional Masonry and the final victory of true hermetic gnosis over incomplete profane knowledge and false doctrines.

And so in the triumphant finale, de Loutherbourg depicts the brave pilgrim, having earned the highest reward for her unwavering steadfastness in the face of adversity. In an ecstatic rush, she ascends the steps of an Egyptian temple shining with otherworldly light, with mere moments remaining until the sacred moment of initiation into the mysteries. Cagliostro-Copt invitingly points his sword to the remaining steps leading to the holy of holies. Above the portal flutters a thin azure veil, penetrated by the blinding rays of transcendent Light of Truth streaming from behind Isis’s partially opened veil. On the colossal stone walls, fragments of mysterious hieroglyphs and magical symbols appear here and there, hinting at the secret, jealously guarded by ancient priests, occult mysteries of the universe and formulas of immortality. To the right of the pilgrim lies the motionless body of the false Mercury — dead or in a deep faint after the crushing defeat in battle with the true Initiator. The neophyte is filled with determination to take the final step, to cross the threshold and, pushing aside the veil, merge with the blinding divine light, finally becoming a perfect Egyptian Mason, worthy of beholding Isis without her veil and obtaining the key to the mysteries of life and death.

This amazing series of watercolors by de Loutherbourg, filled with complex symbolism, became a visible embodiment of the mystical and philosophical ideas that stirred the minds of Enlightenment-era people. In allegorical form, it reflected the characteristic fascination of that time with ancient Egyptian culture, occult knowledge, and esoteric practices that promised to reveal the greatest mysteries of existence, perfect human nature, and grant immortality. Cagliostro’s Egyptian Masonry appeared here as a path of spiritual transformation, leading through mystical death and rebirth to the attainment of higher wisdom and supernatural abilities.

At the same time, de Loutherbourg’s paintings can be viewed as a brilliant example of art synthesis, reflecting the interplay of visual art, theater, literature, religion, and occult-mystical teachings in the pivotal Enlightenment era. They testify to the deep interest of artists and intellectuals of that time in the irrational, supernatural, and mysterious, about their desire to go beyond prosaic reality and connect with hidden dimensions of spiritual experience.

The fate of this unique series of de Loutherbourg’s watercolors and Cagliostro’s London lodge is shrouded in mystery. After the count’s hasty departure from England and his arrest by the Roman Inquisition in 1789, the traces of the paintings are lost. They may have been lost or hidden by some adherents of Egyptian Masonry.

Self-portrait — Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg (1740-1812)

De Loutherbourg himself maintained his interest in occultism, alchemy, and mesmerism until the end of his life. In 1789, he even published a brochure describing his experiments in obtaining gold from base metals and contacts with angels, demonstrating an unchanging attraction to mysticism and the miraculous.

Cagliostro’s tragic end in 1795 in Rome’s Castel Sant’Angelo after imprisonment and torture by the Inquisition only contributed to the posthumous fame of the “Great Copt” and generated many legends about him as a great sage, sorcerer, and innocent victim of the cruel church. The story of the rises and falls of the count-adventurer who dared to challenge the social foundations and religious dogmas of his time attracted the attention of such outstanding writers as Goethe, Schiller, Alexandre Dumas, and Alexei Tolstoy, who created memorable artistic portrayals of Cagliostro in their works.

De Loutherbourg’s watercolors, inspired by Cagliostro’s ideas, remain one of the most striking artistic testimonies of that amazing period in European cultural history, when mysticism, science, magic, and adventurism went hand in hand, and belief in the limitless possibilities of human reason and spirit reached its apex. They give us a chance to peek into the fascinating and mysterious world of hermetic teachings, secret societies, and spiritual quests of the Enlightenment era, a world in which the eternal thirst for Truth and immortality pushed people to the most daring and risky experiments on the edge of possible and impossible. And although the authenticity of Cagliostro’s Egyptian Masonry and the depth of his knowledge in occult sciences remain subjects of debate to this day, the influence he had on the imagination of his contemporaries and descendants is undeniable. Perhaps this is where his true immortality lies — in that particle of eternity that the count-sorcerer managed to breathe into his shining myth, embodied by de Loutherbourg’s brush and celebrated by the greatest poets.